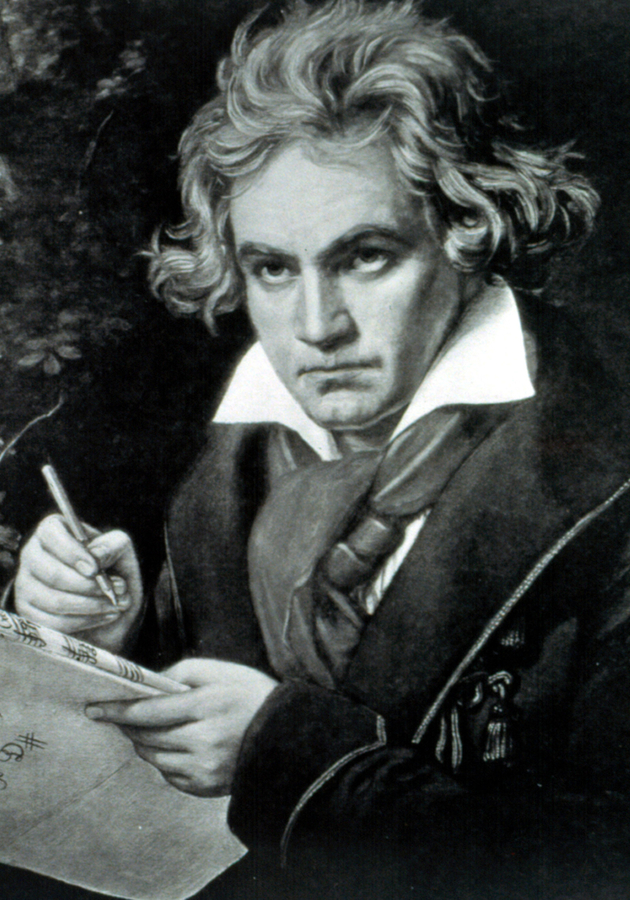

Most symphonies conform to a standardized pattern – they are divided into four long movements of different mood and tempo, which are, in turn, separated by three brief pauses. Ludwig van Beethoven, the greatest composer who ever lived, is inarguably best known for his heightening of the symphonic form. Hence, it seemed like a clever idea to connect the two in this overview. What follows is a colorful portrait of Beethoven’s life and oeuvre, in four biographical movements, three musical intermezzos, two poignant handwritten letters and one thundering finale!

Family and childhood (1770-1784)

Up until his fortieth year, Ludwig van Beethoven insisted he had been born in 1772. His baptismal certificate, however, gives his birth year as 1770. Since it is only the official record of Beethoven’s baptism that has been preserved, his birthday is a matter of conjecture, not of fact. In Beethoven’s birth town of Bonn, it was the custom to baptize on the day following birth. Since the baptism of Beethoven is registered on December 17, there is a consensus (with which Beethoven himself seems to have agreed) that his birthday was December 16. In the absence of documentary proof to the contrary, this date will have to do, for now and posterity.

Beethoven’s family originally belonged to a village near Leuven, in the Flemish Region of Belgium. Probably around 1650, they moved to Antwerp, where in 1685, the name “Van Beethoven” (and variations thereof) makes an appearance in the registers. Unlike the German “von” or the French “de,” the Dutch “van” is not a sign of nobility, but an indicator of a place of origin. Still, until December 1818, Beethoven encouraged – or at the very least permitted to pass unchallenged – the assumption that he was of noble birth. In reality, both his father Johann and his grandfather Ludwig, were lowly and somewhat obscure musicians in the Court band of the Elector of Cologne. They were also inclined to excessive drinking, and something of this passed down to the composer.

Raised in one of the poorest quarters of Bonn, Beethoven grew up a rugged and rebellious child. Unlike Joseph Haydn or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, he didn’t show remarkable genius for the art of music at an early age. In fact, according to diverse witnesses, he showed no spontaneous urge for music at all. However, it must be supposed that his father Johann had seen some indications to the contrary because he began forcing his son into piano lessons ever since his earliest age. “There were few days when Ludwig was not beaten by his father in order to compel him to set himself at the piano,” related one childhood friend of Beethoven. “I can still see him,” an acquaintance of the family agreed, “a tiny boy, standing on a little footstool in front of the clavier to which the implacable severity of Johann had so early condemned him.”

Harsh and unjust, Johann was harboring ambitions to create in his son a prodigy like Mozart, in spite of the boy’s heartbreaking protests and tears. The torture, somehow, succeeded. At the age of 8, Ludwig was displayed in a public concert in Bonn to, apparently, wide acclaim. Four years later, he became the most promising keyboard virtuoso in the Electorate of Cologne, and a talented pupil in composition of the court musician, Christian Gottlob Neefe. He produced his first published work, a set of keyboard variations, in 1783. The following year, Maximillian Francis, the youngest son of Austrian ruler Maria Theresa, was appointed Elector of Cologne. The event changed Beethoven’s life.

Beethoven and Mozart (1784-1787)

Founded a few years before the birth of Christ by Roman legionaries, Bonn is considered one of Germany’s oldest cities. In 1597, it became the seat of the Electorate of Cologne, an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire. Hence, when Maximilian Francis became the Elector of Cologne, he took up his residence in Bonn. A kindly man, he loved two things above all: food and music. In his new position, he was able to enjoy both to an extreme. Just a few years after settling in Bonn, Max Franz (as he was familiarly known) became “the fattest man in Europe.” He also brought together an orchestra of 31 pieces.

Even though lauded as a virtuoso pianist at the time, Beethoven, aged 14, was actually hired to play the viola in Max Franz’s ensemble, with a salary of roughly $750 in today’s money per year. A memorandum dated June 27, 1784, reveals that Beethoven was also listed as “deputy court organist,” and that an idea was entertained of dismissing his teacher Neefe from the ensemble and putting Beethoven in his place as chief organist. Even though this never happened, Beethoven’s talent seems to have been obvious to everybody by this time. A report to the Elector of 1785 described the 15-year-old Ludwig as “of immensely good capability, […] of good, quiet behavior, and very poor.” Endeared to his talents and character, in 1787, Max Franz gave Beethoven both permission and funds for a trip to Vienna for further instruction in musical composition.

The first real event in the life of Beethoven, his visit to Vienna lasted more than three months. Unfortunately, very few dates and details about it are preserved. Even so, the following story may be more than just another anecdote – at least if we are to believe Otto Jahn, a renowned 19th-century biographer of musicians. Namely, soon after his arrival in Vienna, Beethoven was received by none other than Mozart, his musical idol. After being praised in a rather cool manner for the first composition he played (which Mozart thought was a pre-prepared show-piece) the 17-year-old Ludwig begged the famous composer to give him a theme for improvisation. He got one. And then, writes Jahn, “Beethoven played in such an impressive style that Mozart, whose attention and interest grew more and more, finally went silently to some friends who were sitting in an adjoining room, and said, vivaciously, ‘Keep your eyes on that boy. Some day he will give the world something to talk about.’”

Beethoven and Haydn (1787-1792)

Regardless of how the two might have met, Mozart appears to have taken interest in Beethoven and might have even given the adolescent a few piano lessons. Unfortunately, their time together was cut short by two tragic events. First, on May 28, 1787, Mozart’s father Leopold died, and just a week later, Beethoven received news of the severe illness of his mother. He hurried back to Bonn and managed to be at his mother’s bedside when she passed away, on July 17, 1787.

After three months in Vienna, Bonn seemed a little more than a provincial city to the young Ludwig. Fortunately, not long after his return, a German nobleman by the name of Count Ferdinand von Waldstein was admitted to the electoral court in Bonn. A fairly good pianist and composer in his own right, Waldstein noticed Beethoven’s talent early on and resolved to become one of his early patrons. Once, after visiting the young musician in his poor room, he gifted him a new piano. Since, in his pride, Beethoven refused to accept monetary help from anyone but the Court at the time, Waldstein began sending him occasional gifts of money, pretending that they were in fact from the Elector, Max Franz.

At the time, Ludwig needed such help more than ever, since his father, having completely surrendered to alcohol, was thrown out of the Elector’s ensemble on November 20, 1789. Just a few days later, despite still being a teenager, Beethoven became the legal head of his family and took upon himself the responsibility for his two younger brothers, Caspar Karl and Nikolaus Johann. The following month, or more accurately on Christmas Day, Joseph Haydn, the second-best composer in Europe after Mozart, stopped by in Bonn on his way to London to enjoy the performance of one of his Masses by the Elector’s ensemble. Later, at a dinner, on the insistence of Count Waldstein, Max Franz introduced Haydn to Beethoven, maybe even as a potential pupil.

In July 1792, flush with a triumph in London, Haydn again passed through Bonn, this time on his way home to Vienna. Beethoven presented to him a cantata that he had recently composed, possibly on the death of Emperor Leopold II. Haydn enjoyed it greatly and encouraged the young man to proceed with his studies. Probably some word of this reached the Elector’s ear. Prompted by Count Waldstein, he decided to allow Beethoven to go to Vienna to study under Haydn himself, at his own expense. At the time, Ludwig could have asked for no better teacher – a few months before Haydn’s second arrival in Bonn, on December 5, 1791, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died at the tragically young age of 35. Beethoven headed to Vienna to take his place.

Musical intermezzo No. 1: the Bonn compositions

Beethoven’s 1792 album, in which his friends from Bonn inscribed their farewells, amazingly, still exists The most beautiful and prophetic farewell it keeps is that of Count Waldstein, which goes as follows: “Dear Beethoven, you are travelling to Vienna in fulfilment of your long-cherished wish. The Genius of Music is still weeping and bewailing the death of her favorite, Mozart. With the inexhaustible Haydn, she found a refuge, but no occupation, and is now waiting to leave him and join herself to someone else. Labor assiduously, and receive Mozart’s spirit from the hands of Haydn. Your true friend, Waldstein. Bonn, October 29, 1792.” Just three days later, Beethoven left Bonn, as it proved, never to return again.

Thus ended the first period of Beethoven's life. When he left for Vienna, he was a month shy of his 22nd birthday, and he had pretty much nothing of value to show in the music department. Just for comparison, before he was 22, Mozart had written 28 operas, cantatas and masses, and no less than 36 symphonies, including at least one exceptionally mature masterpiece, the “Parisian” in D. At the same age, Beethoven could list under his name no more than 40 compositions in all, and only one work for the orchestra, the “Ritter Ballet” – which he ghostwrote for Count Waldstein in 1791 and allowed him to pass it off as his own. Not until a century later did this fact become evident to musicologists.

A few reasons have been suggested as to why Beethoven matured so late musically. First of all, as already pointed out, Bonn was something of a backwater compared to Vienna, so it’s unlikely that it allowed Beethoven to get acquainted with the mature works of Haydn and Mozart. Hence, most of Beethoven’s early works are stylistically closer to either early Mozart or even inferior musicians, such as those of Italian-born English composer Muzio Clementi. Indeed, that’s pretty much how German musicologist Johann Forkel described Beethoven’s early efforts in a 1784 review. It has been argued that the review hit young Ludwig so hard that he virtually abandoned composition between 1785 and 1790. Truly, only a few works remain from that period.

It would be wrong, however, to suppose that Beethoven didn’t think about great works in Bonn, even if merely in abstract. Just three months after he left for Vienna, a Bonn jurist by the name of Bartholomäus Fischenich wrote the following to one of the sisters of the German playwright Friedrich Schiller: “I enclose a composition on which I should like your opinion. It is by a young man of this place whose talent is widely esteemed, and whom the Elector has now sent to Vienna to Haydn. He intends to compose Schiller's ‘Hymn to Joy,’ and that verse by verse. I expect something perfect: for, as far as I know him, he is all for the grand and sublime.” Glory to Fischenich for being so farsighted! More than 30 years later, Schiller’s “Hymn to Joy” will famously appear in the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Apparently, the great composer had lived with this composition in his mind for pretty much his entire adult life.

The first decade in Vienna (1792-1802)

Other than showing how early Schiller’s “Hymn to Joy” had taken possession of Beethoven, Fischenich’s letter to Schiller’s sister Charlotte is interesting also for the light it throws on the impression which Beethoven had made on those who knew him in Bonn. Despite having not yet produced even a small work, there were apparently people who could credit him with the intention and the ability to produce great, majestical works. This impression, in the opinion of English writer on music Sir George Grove, was doubtless mainly due to the force and originality of Beethoven’s extempore playing, which even at this early age was prodigious, and justified his friends in speaking of him as one of the finest pianoforte-players of the day.

It was as a virtuoso pianist that Beethoven first made a name in Vienna. Future composer Ferdinand Ries, who was also a pupil with Haydn and eventually became one of Beethoven’s closest friends, immediately recognized the talent of Ludwig. “No artist that I ever heard,” he wrote, “came at all near the height which Beethoven attained in piano playing. The wealth of ideas, which forced themselves on him, the caprices to which he surrendered himself, the variety of treatment, the difficulties – all of them seemed inexhaustible under his fingers.” Nevertheless, Haydn, being a classical mind, found it impossible to accept Beethoven’s deviations from orthodox rules of composition. And Haydn was no exception: Beethoven changed four teachers in as many years in Vienna, and all of them found him a difficult disciple, bursting with ideas of his own, and resenting the formalism of the musical theory offered him.

On October 21, 1795, Beethoven published, as his Opus No. 1, the Piano Trios, effectively launching his career as a composer. From then, and until the end of his life, his reputation was such that it allowed him to publish his works at approximately the rate at which he could compose them. As a result, the opus numbers of his compositions are, with only a few trivial exceptions, the true chronological order of his output. For all their fame, Haydn and Mozart weren’t as sought out by publishers. Even less sought out was Franz Schubert, who spent his entire life of 31 years in Vienna in Beethoven’s towering shadow – and not only from the publication standpoint. Case in point, the only time when Schubert could give a concert of his own works in Vienna was in March 1828, on the first anniversary of Beethoven’s death.

Anyhow, Beethoven made a mark as a composer already with his Opus No. 1. English pianist Johann Cramer, one of the best of the age in pure technical perfection, was particularly impressed. After playing the Piano Trios at a meeting of a little Viennese society of musicians, he was moved to shivers and tears. “This is the man!” he cried after the prestissimo finale of the third piano trio. “This is the man who is to console us for the loss of Mozart!” Similar praises for his first major orchestral work, the First Symphony of 1800, gave Beethoven the courage to experiment further with musical forms. However, much more than courage, he needed relief. Because, as his music was consoling the world for the loss of Mozart, Beethoven desperately craved for some kind of consolation himself: unknown to many, as early as 1798, he began losing his hearing.

The first letter: the Heiligenstadt Testimony (1802)

Beethoven was 28 when he first noticed difficulties with his hearing. Ashamed, he kept this a secret from everybody other than his doctor for a long period of time. Finally, in a letter from June 29, 1801, he revealed his condition to a friend of his youth, Franz Wegeler. “For the last three years,” he wrote, “my hearing has become weaker and weaker – and I must confess that I lead a wretched life. I have ceased to attend any social functions, just because I find it impossible to say to people: ‘Speak louder: I am deaf.’ If I had any other profession, I might be able to cope with my illness; but in my profession, it is a terrible tragedy. Heaven alone knows what is to become of me. Only God knows how many times I have cursed Him and my existence…”

On the advice of his doctor – and apparently in hopes of profiting from its sulfur baths – in April 1802, Beethoven moved to the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, just outside of Vienna. One day, wandering in the nearby woods with his friend and then-secretary Ries, he saw, at a short distance, a shepherd playing a pipe. Hearing no sound, Beethoven immediately rushed to his room and wrote, on October 6, 1802, what is known today as the “Heiligenstadt Testament,” one of the most moving and affecting documents in the history of music. Even though addressed to his brothers, the three-page letter was never sent and remained unknown to anyone but Beethoven during his entire life. It was discovered just a few days after his death and published in October 1827, at the 25th anniversary of its composition.

The Heiligenstadt Testament is not, as is often believed, a suicide note. Nevertheless, it is a letter full of depression and distress that shows the full extent of Beethoven’s deep conflict over his sense of artistic mission and his fear of inability to hear normally. It also sounds as a sort of apology for his famously malevolent and misanthropic behavior, which here Beethoven explicitly ascribes to his malady. “Though born with a fiery, active temperament,” he writes, “I was compelled early to isolate myself from people, and forced to live a life in utter loneliness. I find it impossible to say to people: ‘Speak louder, please, shout if you can, for I am deaf!’ Ah, how can I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which should have been more perfect in me than in others!”

A little further down the Heiligenstadt Testament, Beethoven admits that he had even contemplated suicide, but rejected the option due to his self-proclaimed artistic mission. “Trust me,” he explains, “I would have put an end to my life in the past – and it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt was within me, all that I was called upon to produce! So, I choose to endure this wretched existence, hoping my determination will remain firm until the inexorable Goddesses of Destiny cut the thread of my life.” Just a few days later, in a letter to Wegeler, Beethoven made his determination unambiguously known: “Fate shall certainly not crush me completely: I’m telling you: I will seize Her by the throat!”

Musical intermezzo No. 2: the music of the first period

In 1852, Baltic German musicologist Wilhelm von Lenz proposed that the musical development of Ludwig van Beethoven can be best understood if his career is divided into early, middle and late period. Even though the division disregards Beethoven’s apprenticeship years in Bonn, and even though it has been criticized as being misleading countless times, it has remained conventionally recognized to this day. As Sir George Grove remarked decades ago, “that proves that there must be some truth in it, or it would not have been so widely accepted as it is, even by those who differ about its details.” Moreover, Grove went on, Lenz’s division is also “accurate as an expression of the fact that Beethoven was always in progress; and that, to an extent greater than any other musician, his style matured and altered as he grew in life.”

Naturally, the music of what is conventionally thought of as Beethoven’s first period (roughly between the years of 1792 and 1802) reflects the influence of Haydn and Mozart. The major works of this phase are the First and Second Symphonies, the first three Piano Concertos, the first six String Quartets, and more than half of the 32 Piano Sonatas. In them, musicologists distinguish two extremes. On one side, there are compositions that lean strongly toward a deliberate note of public appeal; on the other, there are a few serious and inwardly developed compositions which announce Beethoven’s more mature works. Typical of the first group is Beethoven’s Septet in E-flat major for mixed string and wind instruments (Op. 20), originally dedicated to the Empress Maria Theresa. The first two Symphonies unquestionably belong to the second group, as does “the Moonlight Sonata” (Op. 27) and “the Sonata Pathétique” (Op. 13), neither of which was named so by Beethoven.

Regardless of which of the two groups they belong to, most of Beethoven’s early Vienna works employ the principle of formal structure associated with the classicism of Mozart and Haydn. In many of them, writes Grove, “there are melodies and passages that might be almost mistaken for theirs, with compositions apparently molded in intention on them. And yet,” he adds, “even during this Mozartian epoch, we meet with works or single movements which are either not Mozart, which Mozart perhaps could not have written, or which very fully reveal the future Beethoven.” Such are the first two movements of the Sonata in A major (Op. 2), the Grand Sonata (Op. 7), the Scherzos of the 1st and 2nd Symphonies, and a few others. Near the end of his first phase, Beethoven composed the Kreutzer Sonata (Op. 47), notable for its technical difficulty and emotional scope. However, it was with his Third Symphony, the famous “Eroica,” that he finally left Mozart and Haydn behind and moved on to his mature period – the heroic years.

Tearing up the rule book: Eroica (1803-1805)

Beethoven began to plan his Third Symphony in the autumn of 1802, produced a complete piano score by October 1803 and had an orchestrated version by early summer 1804. The work was first performed privately at the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz, one of Beethoven’s patrons and sponsors, and then given its public premiere at the Theater-an-der-Wien, on April 7, 1805. Despite his defective hearing, Beethoven conducted the performance himself. In line with his character, and against all contemporary conventions, the style of his conducting was excitable, demanding, and most extravagant. As Grove beautifully illustrates, “At a pianissimo, he would crouch down so as to be hidden by the desk, and then as the crescendo increased, would gradually rise, beating all the time, until at the fortissimo, he would spring into the air with his arms extended as if wishing to float on the clouds.”

The first performance of the “Eroica” broke boundaries and audience expectations. Everything from its shape to its length, from its form to its arrangement, from its harmonic tensions to the huge range of keys it employed sounded original and surprising to early listeners – far from how a symphony was supposed to work. Predictably, most of the audience members at the premiere didn’t like it. “I’ll give another kreuzer,” said one out loud during the first pause, “if the thing will only stop playing!” He had a point: the first movement of the “Eroica” was more developed and longer than many entire symphonies written before. In a very brief time, however, it came to be valued in its own right, for its novel sensibility, its strong dissonances and its atypical shape. The same can be said of the entire symphony as well. Although initially criticized as a work of “undesirable originality,” it soon came to be appreciated as a work of profound genius and was to exert a huge influence on later generations of symphonists, from Robert Schumann to Gustav Mahler.

There is, of course, another, even more famous, story related to the first performance of “Eroica” – or more particularly to its title. Namely, as relayed by Ries, Beethoven had intended to dedicate his Third Symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he believed to be champion of people and bringer of liberty. Ries was the first to tell Beethoven that Napoleon had proclaimed himself the Emperor of France, not long before the first performance of the “Eroica.” Thereupon, Beethoven flew into a rage and cried out: “Is then he, too, nothing more than an ignoble human being? He will now trample on all the rights of man and indulge only his ambition! He will exalt himself above all others, he will become a tyrant!” After saying this, Beethoven went to the table, took hold of the title-page by the top, tore it in two and threw it on the floor. The first page was rewritten the following day, and only then did the symphony receive its full title: “Heroic symphony: in celebration of the memory of a once great man.”

The heroic years: an age of masterpieces (1803-1809)

Soon after the “Eroica,” Beethoven lost virtually all ability to hear, but his musical genius only flourished in the years that followed. His Third Symphony didn’t just change the rules of the game, but pretty much rewrote the entire rulebook. Before the “Eroica,” composers were expected to show some respect for the audience, the performers and, above all, the conventions. That’s why contemporary listeners didn’t have problems accepting Haydn or Mozart – their harmonies were easy on the ear because they shared many characteristics with their precursors. What distinguished Beethoven’s Third Symphony so much was its highly individual character. “After the ‘Eroica,’” wrote American musicologist Joseph Kerman in 1967, “Beethoven’s compositions become to a cardinal degree pointed individuals. A mature Beethoven piece is a person; one meets and reacts to it with the same sort of particularity, intimacy and concern as one does to another human being.”

The thing about people is that it takes time and effort to get to know them, let alone learn to like them. That explains the destiny of Beethoven’s only opera. Originally titled “Leonore, or the Triumph of Marital Love” the opera premiered just a few months after the “Eroica,” on November 20, 1805. The performance was a failure. Once again, Beethoven was told by critics that his work was too long and, moreover, clumsily arranged. This time, however, he listened. With the help of librettist and friend Stephan von Breuning, he shortened the opera from three acts to two and offered the work a second time on March 29, 1806; again it failed. After further work on the arrangement and the libretto, a final version, bearing the new title of “Fidelio,” was performed at the prestigious Kärntnertortheater on May 23, 1814. This time, it achieved success.

Between the “Eroica” and “Fidelio,” Beethoven gave the world such masterworks as the Piano Sonata No. 23 in F Minor (later christened “Appassionata”), the Piano Concerto No. 5 in E Flat (today known as the “Emperor Concerto”) and, of course, the Fifth and the Sixth Symphony, commonly referred to as the Fate Symphony and the Pastorale. These last two received their premiere together on December 22, 1808, in a four-hour benefit concert which also included the Fourth Piano Concerto and the Choral Fantasy. Even though the concert occurred in a very cold hall, and even though the Choral Fantasy had been insufficiently rehearsed and had to be restarted mid-performance, the event was a resounding success. Essentially, it underscored what most music lovers had already realized soon after the “Eroica” – that Beethoven was Europe’s greatest composer, and that he had boldly ventured into some uncharted musical territories.

Beethoven and Goethe (1809-1812)

At the end of 1809, the Burgtheater commissioned Beethoven to write incidental music for a revival of “Egmont,” a 1788 play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He accepted the job with enthusiasm: just like most of the German world at the time, Beethoven was a great admirer of Goethe. The final result – an overture, and nine additional entr'actes and vocal pieces (Op. 84) – was deemed fitting of both Goethe’s Shakespearean pathos and Beethoven’s heroic style. In the years which followed, Beethoven developed further interest in Goethe, setting three of his poems as songs (Op. 83) and often discussing his other works with Elisabeth “Bettina” Brentano, a mutual acquaintance of the poet and the composer. On May 28, 1810, Brentano wrote an enthusiastic letter about Beethoven to Goethe, describing him as someone who made her forget the world and all other art. “He stalks far ahead of the culture of humankind,” Brentano told Goethe. “He believes, rightly, that he is the Bacchus who makes humanity spiritually drunk with music.”

According to the letter, Beethoven had asked Brentano to tell Goethe that “music is the one incorporeal entrance in the higher world of knowledge,” and that this idea is something he would enjoy discussing in person with the great author. Goethe replied cordially, and invited Beethoven to what was then called Karlsbad and is today known as Karlovy Vary, a spa resort in today’s Czech Republic. Due to serious illness, Beethoven was unable to get to Karlsbad in 1811, but the following year, the two great artists finally met in the neighboring spa town of Töplitz (today’s Teplice). Goethe’s first impression of Beethoven, as shared with his wife in a letter, was one of awe: “A more self-contained, energetic, and sincere artist I have never seen. I can understand right well how singular must be his attitude toward the world.” Beethoven wasn’t as impressed: “Goethe is too fond of the atmosphere of the court,” he told his publisher, “and certainly more so than is becoming to a poet.”

A famous anecdote beautifully illustrates this difference between the two great artists. One day, while they were walking around the spa resort, there came toward them the Empress of Austria and the Archdukes, who were also in Töplitz at the time. Seeing them, Beethoven said to Goethe: “Keep hold of my arm: they are the ones who should make room for us, not we for them.” Goethe was of a different opinion, and the situation became awkward for him. At the final moment, he let go of Beethoven’s arm and took a stand at the side with his hat off. Beethoven, in contrast, walked right through the dukes and only tilted his hat slightly. The dukes had no choice but to step aside and make room for the composer; nevertheless, they all greeted him pleasantly. “Well, Johann” Beethoven said afterward, “I honor and respect people as they deserve. However, you seem to give some unworthy individuals too much honor. It’s easy to make an archduke. But you can’t make a Goethe or a Beethoven.”

The second letter: the Immortal Beloved (1812)

When Beethoven arrived in Töplitz in the summer of 1812, he was ill, heartbroken, and anxious about his finances. When he left the spa resort in the autumn, he was full of ideas and brimming with energy. But it wasn’t because of Goethe. Yes, the company of the poet suited Beethoven and yes, the two colossi of European culture had enjoyed each other’s company. However, they were just too different to become anything other than acquaintances. Even though they had discussed collaborating on an opera in Töplitz, nothing came of the plans. Once the two men had returned home – Beethoven to Vienna, Goethe to Weimar – they pretty much stopped communicating with each other, while keeping their admiration for each other. Their clashing temperaments provided too great an obstacle to friendship.

So, once again, it wasn’t Goethe who altered Beethoven’s temper. Unfortunately, to this day, we still don’t know who it was. We do know it was a woman – and a married one to boot! We also know that, for a few days of the month of July in 1812, she was repeatedly unfaithful to her husband. Other than that, however, we know virtually nothing. We would have probably known even less had the executors of Beethoven’s will not found an unsent letter in the composer’s estate following his death. Addressed to “the Immortal Beloved,” the letter is written in pencil, on 10 small pages, and consists of three parts. In the first part, Beethoven looks forward yearningly to a secret meeting with his beloved and wonders how many sacrifices might their love need to endure. The second part ends with a beautiful image: “Oh God! so near so far! Is it not a real building of heaven, our Love – and as firm, too, as the citadel of heaven!”

We can quote a bit more from the third part of the letter, the most touching. “Even in bed my ideas yearn towards you, my Immortal Beloved,” writes Beethoven. “I can only live, either with you or not at all. Yes, I have determined to wander about through life, until I can send my soul enveloped by yours into the realm of spirits. I regret it, but this must be. You will get over it all the more as you know my faithfulness to you: never another one can own my heart, never – never! O, God, why must one go away from what one loves so? Your love made me the happiest and unhappiest at the same time. Love me – today – yesterday!” A warmly sexual man, Beethoven enjoyed numerous romantic liaisons before Töplitz. Afterward, however, there are no reports of a similar kind. He did resort to prostitutes from time to time, but, otherwise, he seems to have kept his promise to the Immortal Beloved until his dying breath. Who was she? No one knows.

Musical intermezzo No. 3: Beethoven’s heroic style

Beethoven’s return to Vienna from Töplitz in 1812 was as transformative as his return from Heiligenstadt a decade before: both were marked by definite changes in his mood and his musical style. Hence, between these two events, we can safely frame the second, middle period of Beethoven’s musical career. It is usually called “heroic,” after the symphony which announced it, the “Eroica;” but also because it is characterized by many original works composed on a grand scale. Before Heiligenstadt, Beethoven saw himself as a tragic victim and tried composing in spite of his gradual loss of hearing; afterward, he saw himself as a tragic hero and began composing through his ever-worsening malady. In one of his 1806 musical sketches, there stands a revealing note: “Let your deafness no longer be a secret – even in your art!” A while before, he told one of his pupils the following: “I am not satisfied with the work I have done so far. From now on, I intend to take a new way.” And indeed, he did.

“In his second period,” writes historian of culture Will Durant, “Beethoven made greater demands upon the performers in tempo, dexterity, and force; he explored contrasts of mood from tenderness to power; he gave rein to his inventiveness in variation, and to his flair for improvisation, but he subjected these to the logic of affiliation and development; he changed the sex of the sonata and the symphony from feminine sentiment and delicacy to masculine assertiveness and will. As if to signalize the change, Beethoven now replaced the old third movement of the symphony, the minuet, with a dynamic scherzo, frolicking with notes, laughing in the face of fate. Now he found in music an answer to misfortune: he could absorb himself in the creation of music that would make the death of his body merely a passing incident in an extended life.”

The musical compositions of Beethoven’s heroic period are masterworks in defiance of Fate. “Only when I am playing and composing, I can live with my affliction,” he wrote in 1806. The result was not only prolificacy, but also quality. In the words of Grove, Beethoven’s middle period was “a time of extraordinary greatness, full of individuality, character, and humor, but still more full of power and mastery and rebelliousness and pregnant strong sense.” Running from the “Eroica” to the final version of “Fidelio,” the second period of Beethoven includes his sole opera and all symphonies but the first two and the last one. It also includes the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos; the last Violin Sonata (Op. 96); the Piano Sonatas from Op. 53 to Op. 90; and the remarkable Mass in C Major (Op. 86). Somewhere around the end of this heroic age, Beethoven grew completely deaf. The rest, however, wasn’t silence. The great composer wasn’t done just yet.

Portrait of an aging composer (1812-1818)

After 1812, personal problems became a major barrier between Beethoven and the Viennese high society. First of all, there were some issues of honor: Ludwig’s youngest brother Johann had begun living with a woman who had an illegitimate child with someone else. In an attempt to save his family name, Beethoven tried, but was unable to convince Johann to end the relationship. Then there followed a family tragedy: in 1815, Ludwig’s other brother Kaspar died from tuberculosis. As a result, Beethoven became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Kaspar’s wife Johanna over the custody of their son Karl, then 9 years old. Eventually, he won the dispute and became a legal guardian of his nephew. Karl, however, proved to be erratic and unstable, so he became another source of anxiety for the already vulnerable Beethoven. Finally, there was also his deafness, owing to which, in 1815, Beethoven was compelled to give up all hope of performing publicly as a pianist.

During these years, Beethoven became a living embodiment of the artist beyond society. Generally neat, he stopped caring altogether about his appearance and public manners. He began railing openly against the nobility, the courts, and the Emperor of Austria himself, either oblivious of the possible consequences or not concerned at all. “He defies everything and is dissatisfied with everything and blasphemes against Austria,” wrote one of his doctors in 1816. A little later, Franz Grillparzer, the leading Austrian dramatist of the age, reported that when irritated, Beethoven “became like a wild animal,” and even labeled him “half crazy.” Conductor Carl Friedrich Zelter used only the last of these two words to describe the composer to Goethe in an 1819 letter. Indeed, by then, Beethoven had even stopped trying to hold back the rumors. Once, he was mistaken for a beggar by a policeman. It didn’t help that, a year before, he had begun carrying blank booklets with him, for his friends and acquaintances to jot their sides of conversations, while he answered out loud.

Around 1815, Beethoven’s physical health began to deteriorate as well. Ultimately, he developed cirrhosis of the liver, which was no doubt accelerated by his reckless lifestyle. Specifically, as the years saddened him, he yielded more and more to the amnesia of wine – just like his father had before him. The world had changed – and he couldn’t understand it anymore. Moreover, it didn’t seem fit any longer for the majestic style of his heroic years. The Treaty of Vienna, signed just days before Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, was a great victory for the traditional monarchs of Europe and a crushing defeat for Beethoven and the liberal movements of the continent. Consequently, between 1815 and 1818, the composer’s output dropped to the lowest level of his adult life. In retrospect, though, these years seem more like the proverbial calm before the storm. The silence didn’t mean, as others had supposed, that Beethoven had given up composing – rather, that he was slowly forging his way into the world of his final phase.

The last masterpieces (1818-1827)

The composition which formed a bridge between Beethoven’s middle and last period was his 29th Piano Sonata (Op. 106), known more simply as the Hammerklavier Sonata. Widely viewed as one of the most important works of Beethoven and among the greatest piano sonatas of all time, the Hammerklavier is also considered to be the most demanding solo work in the classical piano repertoire. Among other precedents, it set one for the length of solo compositions: depending on interpretive choices, the third movement alone can last more than 30 minutes! As German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche commented, only half-jokingly, the Hammerklavier is less a sonata than it is a symphony. “We must correct Beethoven’s mistake,” he wrote in the 173rd aphorism of “Human, All Too Human.” “A master of all orchestral effects must restore to life the symphony which here had suffered an apparent pianistic death.”

The Hammerklavier was recognized as the summit of piano literature almost immediately after its first publication. However, it was also deemed too difficult for performance, so its first documented public presentation happened nine years after Beethoven’s death, when Franz Liszt played it in Paris. Fortunately, Beethoven did have a chance to enjoy several other musical triumphs during his marvelous musical resurgence of the final phase. The last and the greatest of them all occurred on May 7, 1824. On a calm Friday evening, an audience of about one thousand Viennese gathered in the Theater am Kärntnertor to hear, for the first time, three parts of Beethoven’s matchless Missa solemnis, and the entirety of his incomparable Ninth Symphony, one of the supreme achievements in the history of music. Involving the largest orchestra ever assembled by Beethoven, the concert of 1824 was undoubtedly his greatest triumph as well.

Beethoven wasn’t just present at the performance: he was also conducting the orchestra on the stage. However, two years earlier, Michael Umlauf – the official conductor of the concert – had seen Beethoven’s disastrous attempts to conduct a dress rehearsal of his opera “Fidelio” and instructed the musicians to ignore him. Umlauf did well, since at the end of the Ninth Symphony, when the audience began to applaud enthusiastically, Beethoven was still conducting, “throwing himself back and forth like a madman.” One of the singers, the Austro-Hungarian contralto Caroline Unger, walked over to the composer and turned him around. Tears came streaming down the face of Beethoven when he saw the cheers and the applause. There were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and many raised hands. The Viennese knew that Beethoven couldn’t hear them, so they made sure that he would be able to see the ovations.

The music of Beethoven’s final phase

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was the first example of a major composer using voices in a symphony. The words sung during its final movement are taken from Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” that same poem that took hold of Beethoven in his early twenties in Bonn. It was a fitting finale – to a supreme musical career, to four decades of incessant experimentation and artistic evolution, to life, to death, to everything! Long a revolutionist, with the last of his symphonies, Beethoven finally emerged a victor from his lifelong war against classical norms, while welcoming the Romantic movement into music. He didn’t just give the symphonic form an even looser structure than the one the “Eroica” had outlined two decades before, but he also succeeded in subordinating almost all old rules to “a rampant freedom of emotional and personal expression.”

In the words of Will Durant, “Something of the wild spirit that had spoken in France through Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Revolution, in England through the poetry of Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge, and in Germany through young Goethe’s ‘Werther’ and young Schiller's ‘The Robbers,’ – something of all this came down to Beethoven, and found rich soil in his natural emotionalism and individualistic pride. An old system of law, convention, and restraint collapsed in art as in politics, leaving the resolute individual free to express or embody his feelings and desires in a joyful bursting of old rules, bonds, and forms. Beethoven mocked the masses as asses, the nobles as impostors, their conventions and courtesies as irrelevant to artistic creation; he refused to be imprisoned in molds fashioned by the dead, even by such melodious dead as Bach and Handel, Haydn and Mozart. He made his own revolution, even his own Terror, and made his ‘Ode to Joy’ a declaration of independence even in expectation of death.”

“To attempt to characterize any truly significant aspects of Beethoven’s last works in a few words would be beyond effrontery,” says a modern biographical encyclopedia. “Their vastness and imaginative complexity baffled not only his contemporaries but later audiences and even professional musicians for some time after Beethoven’s death. In various ways, they seem the fully logical outcome of a lifetime of deep exploration of the possibilities of tonal structure; in other ways, they seem to exceed in depth almost any of Beethoven’s other music and perhaps that of any other subsequent composer.” Beethoven himself was fully aware that they were beyond the capacities of the musicians of his age. “Do you think I care about your wretched fiddle when the Muses speak to me,” he told a violinist who was struggling to learn one of his late string quartets. To another one, equally bewildered by them, the calmer Beethoven is reputed to have said something even more memorable: “Worry not, they are not for you – they are for a later age.”

The grand finale: the death and immortality of Beethoven

Composed between 1825 and 1826, Beethoven’s late string quartets, six in all, were his last major completed compositions. As already revealed, they went far beyond the comprehension of musicians and audiences of his time. “We know there is something there,” said one violinist, “but we do not know what it is.” Composer Louis Spohr called them “indecipherable, uncorrected horrors.” Nevertheless, they are widely revered today among experts. Many musicians consider them “the greatest music of the greatest composer who ever lived,” and some have even described them as “the pinnacle of Western civilization.” Schumann once wrote that they stand “at the extreme boundary of all that has been attained by human art and imagination.” It is said that Beethoven himself deemed the third of the string quartets, Op. 131, his most perfect single work. The same composition was Schubert’s last musical wish. After it finished, lying on his deathbed, he sighed a famous remark: “Oh, beautiful… After this, what is left for us to write?”

Nothing, indeed. Soon after completing the string quarters, on December 2, 1826, Beethoven contracted pneumonia, from which he never fully recovered. For the following four months, he remained bedridden and died from cirrhosis of the liver in Vienna, on March 26, 1827. Even his death was gloriously heroic. Three days before passing away, Beethoven signed his will and whispered to the friends gathered around his deathbed: “Plaudite, amici, comedia finita est,” – Latin for “Applaud, my friends, this comedy has finally ended.” Then, just before he died, a flash of lightning illuminated his room, followed by a sharp clap of thunder. After this unexpected phenomenon of nature, Beethoven suddenly raised his head, and stretched out his own right arm majestically – like a general giving orders to an army. According to a witness, it seemed as if he wished to call out to his wavering troops: “Courage, soldiers! Forward! Trust in me! Victory is assured!” This lasted but for an instant; then, Beethoven’s arm sunk back; then, he fell back; the musical genius, the greatest composer of history, was no more.

Whatever it meant, Beethoven’s last gesture was certainly one of defiance – Just like his entire life, just like his entire oeuvre. His greatest achievement, however, wasn’t that he created some of the greatest musical works ever composed; nor was it that he redefined several musical genres in merely a few decades. The fact is that a few other musicians can claim similar feats. Beethoven’s unique contribution was far greater than theirs: he managed, almost singlehandedly, to raise instrumental music, hitherto considered inferior to vocal, to the highest plane of art. Through an abundance of talent and genuine belief in the power of art, he reinvented music from “the art of pleasing sounds” to “the art all other arts aspire to.” In the process, he reinvented himself as well, at least three times across the span of a tumultuous life. Never willing to stand still, refusing to repeat himself, Beethoven attained immortality through constant growth in the face of boundless suffering. In doing so, he outgrew his human form and became what few ever have – an archetype, a legend, a myth.

Sources

Main

- Alexander Wheelock Thayer, The Life of Ludwig van Beethoven, Volumes I-III [additional translations by Henry Edward Krehbiel] (New York: The Beethoven Association, 1921).

- Maynard Solomon, Beethoven, 2nd edn (New York: Schirmer Books, 2011).

- George Grove, “Beethoven, Ludwig van,” A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450-1880), Vol. I [ed. George Grove] (London: Macmillan and Co., 1879), pp. 162-209.

- Will Durant, “Beethoven (1770-1827),” The Story of Civilization, Vol. XI: The Age of Napoleon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), pp. 567-586.

- Knapp, Raymond L. and Budden, Julian Medforth, “Ludwig van Beethoven,” Encyclopedia Britannica (March 22, 2021) [https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-van-Beethoven].

- “Beethoven, Ludwig van,” Encyclopedia of World Biography [ed. Paula K. Byers, Suzanne M. Bourgoin, and Neil E. Walker], 2nd edn (Gale, 1998), Vol. II, pp. 114-118

Other

- Ludwig van Beethoven, “Immortal Beloved,” Letters of Note (June 10, 2011). [https://lettersofnote.com/2011/06/10/immortal-beloved/]

- “I live only in my notes,” The Classical Music Book (New York: DK, 2018), pp. 138-141; p. 139.

- Maynard Solomon, “Beethoven: The Nobility Pretense,” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Apr. 1975), pp. 272-294.

- Alan Tyson, “The Hammerklavier Sonata and Its English Editions,” The Musical Times Vol. 103, No. 1430 (April 1962), pp. 235-237.

- Will Crutchfield, “Did Music Hit Its Peak with Mozart?” The New York Times (July 8, 1984). [https://www.nytimes.com/1984/07/08/arts/did-music-hit-its-peak-with-mozart.html]

- John Rockwell, “Beethoven Quartets Pose the Challenge Of Greatness,” The New York Times (July 10, 1983). [https://www.nytimes.com/1983/07/10/arts/recordings-beethoven-quartets-pose-the-challenge-of-greatness.html]

- Alex Ross, “Deus ex musica,” New Yorker (October 13, 2014). [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/10/20/deus-ex-musica]

- Sudip Bose, “When Beethoven Met Goethe,” The American Scholar (July 27, 2017). [https://theamericanscholar.org/when-beethoven-met-goethe/]

- John Suchet. “Beethoven's patrons: Count Waldstein,” Mad About Beethoven. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. [http://www.madaboutbeethoven.com/pages/people_and_places/people_patrons/people_patrons_waldstein.htm]

- Iulian Munteanu, “Beethoven's Heiligenstadt Testament,” All About Beethoven. [https://www.all-about-beethoven.com/heiligenstadt_test.html]